A Philosophy of Building Better - Chapter 3: There is an Objectively Correct Way to Build

The School of Athens by Raphael

“When I perceive something with the bodily sense, such as the earth and sky and the other material objects that I perceive in them, I don’t know how much longer they are going to exist. But I do know that seven plus three equals ten, not just now, but always; it never has been and never will be the case that seven plus three does not equal ten. I therefore said that this incorruptible truth of number is common to me and all who think.”

St. Augustine, On Free Choice of the Will

Hi all 👋

In a previous post, I introduced my new writing project, Building Better. This will be my final post that I will cross-post onto A Berg’s Eye View, so if you would like to subscribe to future posts, please consider subscribing to support my work!

Thanks!

Erik

Today we continue our series outlining the Philosophy of Building Better:

Chapter 2 - The Purpose of Building is to Further Human Flourishing

Chapter 3 - There is an Objectively Correct Way to Build

Chapter 4 - Building is Fundamentally Contextual

Chapter 5 - The Builder Must Learn from the Great Builders of the Past

Chapter 6 - Building Better Supports People’s Best Impulses

Chapter 7 - The Better Builder Refuses to Ethically Compromise

Chapter 8 - The Better Builder Strives to Repair

Chapter 9 - The Builder’s Oath

Chapter 10 - The Building Better Checklist

The purpose of this post is to convince you that there is an objectively correct way to build.

In order to do this, I first need to convince you that objectivity exists. This is a massive question (one of, if not the, most important questions in the history of philosophy). You could write an entire book on just this topic alone, and trying to settle it in a digestible post is ultimately impossible. I am going to do my best by highlighting the arguments of some of the great philosophers of history, but just know that I’ll be scratching the surface and that there are countless opportunities to explore further.

If you pay attention to the popular narrative in our modern society, you would likely come away with the impression that objectivity doesn’t really exist. The modern discourse explicitly and implicitly suggests that “perception is reality”. It advocates for a form of subjectivity that precludes the expressing of judgment on whether an action is right or wrong. Not “the truth”, but “your truth”. This narrative may seem new, but attempts to challenge objective truth are as old as recorded history.

Early Ionian nature philosophers such as Thales, Anaximander, and Heraclitus all developed beliefs about how the world worked based on observing natural phenomena.1 Parmenides was one of the first thinkers to raise questions about the veracity of observed reality in a world where he believed nothing was ever created or destroyed.

The first philosopher to address this tension between perception and reality was Plato who created a metaphysics that synthesized the two seemingly incompatible concepts. He does this, not by attacking Parmenides’ idea that perception is flawed but by synthesizing it with a view of unchanging, universal truth more akin to Heraclitus’ logos.

In Plato’s metaphysics, most popularly captured in his Allegory of the Cave, the perceived world is transient. All things change and eventually wither away and die. But there is another unseen world where objective, universal truth exists. Plato calls this the World of the Forms. If you were to look out your back window at a tree, you would be observing a particular tree. This tree would be in a constant state of flux as parts of it grow and other parts die, never being exactly the same at any point in time as it was at a previous point in time. But if you sat inside and thought of the idea of the tree, you would be contemplating the Form of the Tree. The Form of the Tree is the universal understanding of what a tree is and all particular trees receive their “tree-ness” by participating to various degrees in that universal form of the Tree. Unlike any particular tree that you may observe, the Form of the Tree does not change over time and will never decay. Plato’s metaphysics is a critical step forward in the case for objective truth as it allows for both flawed perception of the physical world around us and the objective truth of an unseen and unchanging world.

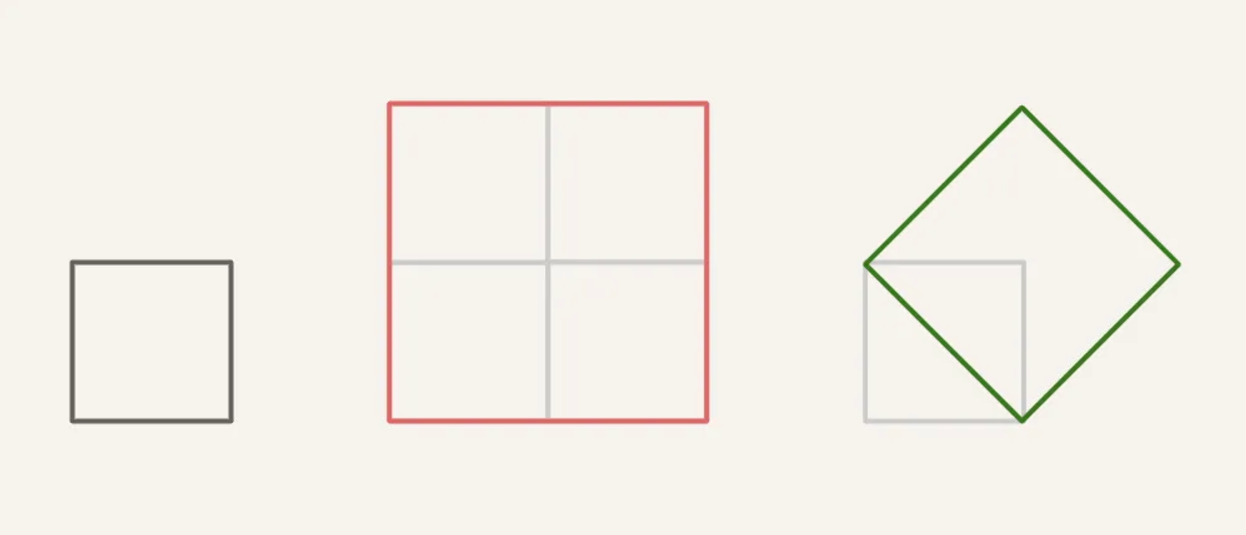

Plato’s next argument for objectivity is based on the objective truths of math.2 In the dialogue, Meno, Socrates claims that truth exists outside of our individual perception. He demonstrates this by asking a servant to find a square exactly twice as large as one that he has drawn on the ground. Through trial and error, the servant eventually arrives at the correct answer.

Plato uses this example to show that math is an undeniable objective truth that exists outside of perception. A square formed by the diagonal of another square is always exactly twice the area of the original square. It doesn’t matter how big the first square is or whether it is drawn in sand or simply imagined in your mind. This truth is true in all circumstances. In math, Plato finds an example of the existence of objective truth, and if objective truth exists, then the assertion that everything is subjective is demonstrably false.

A proponent of subjectivity may argue that while objective truth exists in some fields such as math, physics, or musical theory, it does not exist in other fields such as ethics or building.

The philosopher and theologian St. Augustine of Hippo addresses this argument by asking the question:

You surely could not deny that the uncorrupted is better than the corrupt, the eternal than the temporal, and the invulnerable than the vulnerable.3

Augustine argues that in all things there is an ordered gradient. Some qualities or things are objectively better than others. You can judge the quality of something by how well it fulfills its purpose. If the purpose of an apple is to be eaten, then a ripe apple is always better to eat than a rotten apple. It is not a subjective matter, but an objective one. Once we understand the purpose behind something, there will always exist an ordered gradient of better ways to fulfill that purpose than others.

To discuss how this objectivity applies to building better, I want to tell you about a timeless way of building.

Christopher Alexander was an American architect, professor, and theorist. In his book The Timeless Way of Building he explores why we seem to have lost the ability to build great buildings and how we can get back to doing so. All the great wonders of the past were built with far less technological knowhow and sophisticated techniques, and yet they contain an awe inspiring quality that is unmatched by modern construction. Compare the Gothic Notre-Dame de Paris to the Neo-Gothic Hallgrímskirkja. Both are striking examples of religiously inspired architecture, but there is a lifelike quality infused into Notre-Dame that is utterly lacking in the striking but sterile Hallgrímskirkja.

We can make buildings faster, bigger, and more efficiently than ever before and yet there is something that has been lost in the scaled, modularized, approach to building that is so commonplace today. Alexander refers to that “something” that has been lost as the “quality without a name”.

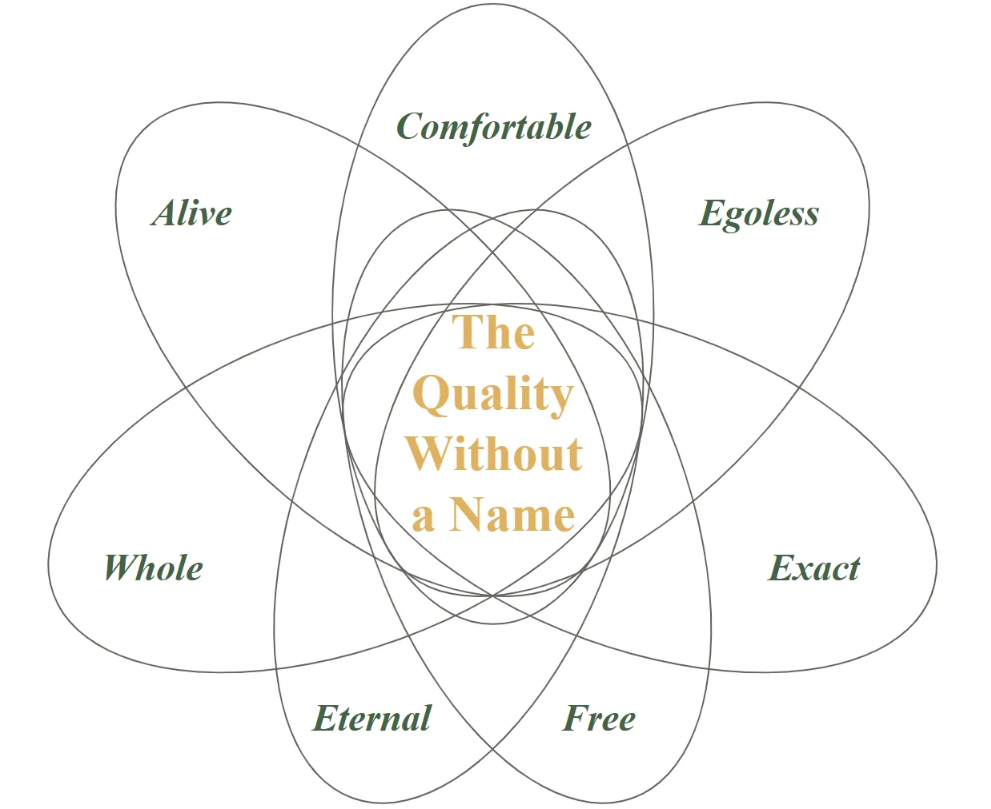

There really isn’t a word that perfectly captures it. Alexander tries the words alive, whole, comfortable, free, exact, egoless, and, eternal. They all capture aspects of the quality without a name, without any being able to fully encapsulate its meaning. For example, the word “whole” captures the self-sustaining aspect of the quality without a name, but it gives off a connotation of being too self-enclosed. The word “comfortable” captures how we feel in spaces that contain the quality without a name but there can be things which are too comfortable and become overly static.4

The quality without a name is the quality that occurs when the competing forces in a given context are resolved and the system is whole. It is at one with itself and free from inner-contradictions. Alexander argues that all the great buildings of the past, and in fact most pre-modern buildings, contain this quality.

Alexander does not, however, think of this quality as some subjective matter left up to an individual’s personal taste. He believes this quality to be objective, discernible, and measurable.

There really are good acts of building and bad ones. Ones that nudge the world in a better direction and ones that shift it in a worse direction. Even if we accept that objectivity truly does exist and that there can be good and bad acts of building, we are left with another question: how are we to determine whether a building is good or not?

Alexander’s answer is to be aware of how we feel in that building. When we are in a place that contains the quality without a name, we feel better. We are filled with a sense of connection to the world around us. A sense that things are as they should be. This feeling can be felt both somewhere majestic like Notre-Dame and in a sleepy log cabin. Alexander argues that this feeling is not some wishy-washy personal preference, but instead that it is measurable, repeatable, and shockingly consistent across people and cultures.

If we accept that there really are some buildings that are objectively better than others, Alexander’s work provides a roadmap for us to apply to all of our various acts of building.

I believe that there really are better patterns.

Patterns for building things that make us feel whole and resolve the inner forces surrounding us.

In Chapter 1, we discussed how every single one of us is a builder. In Chapter 2, we argued that the ultimate purpose of all acts of building is to further human flourishing. In today's post we have examined the concept of objectivity and how it can be applied to recognize good building patterns from bad ones.

In the future chapters we will discuss much more about how to recognize this timeless way of building and strategies to apply it to all of our acts of building.

Let’s Build Better,

Erik

1 - Unless otherwise stated, background information comes from the Fifth edition of Norman Melchert’s The Great Conversation. I highly recommend this textbook to anyone who is interested in developing a broad understanding of the historical development of philosophy.

2 - From Meno

3 - Augustine, On Free Choice of the Will

4 - Apparently in his later work Nature of Order Alexander begins to call this quality “wholeness”